Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Mini is Beautiful: CUHK’s trailblazing minimally invasive surgery

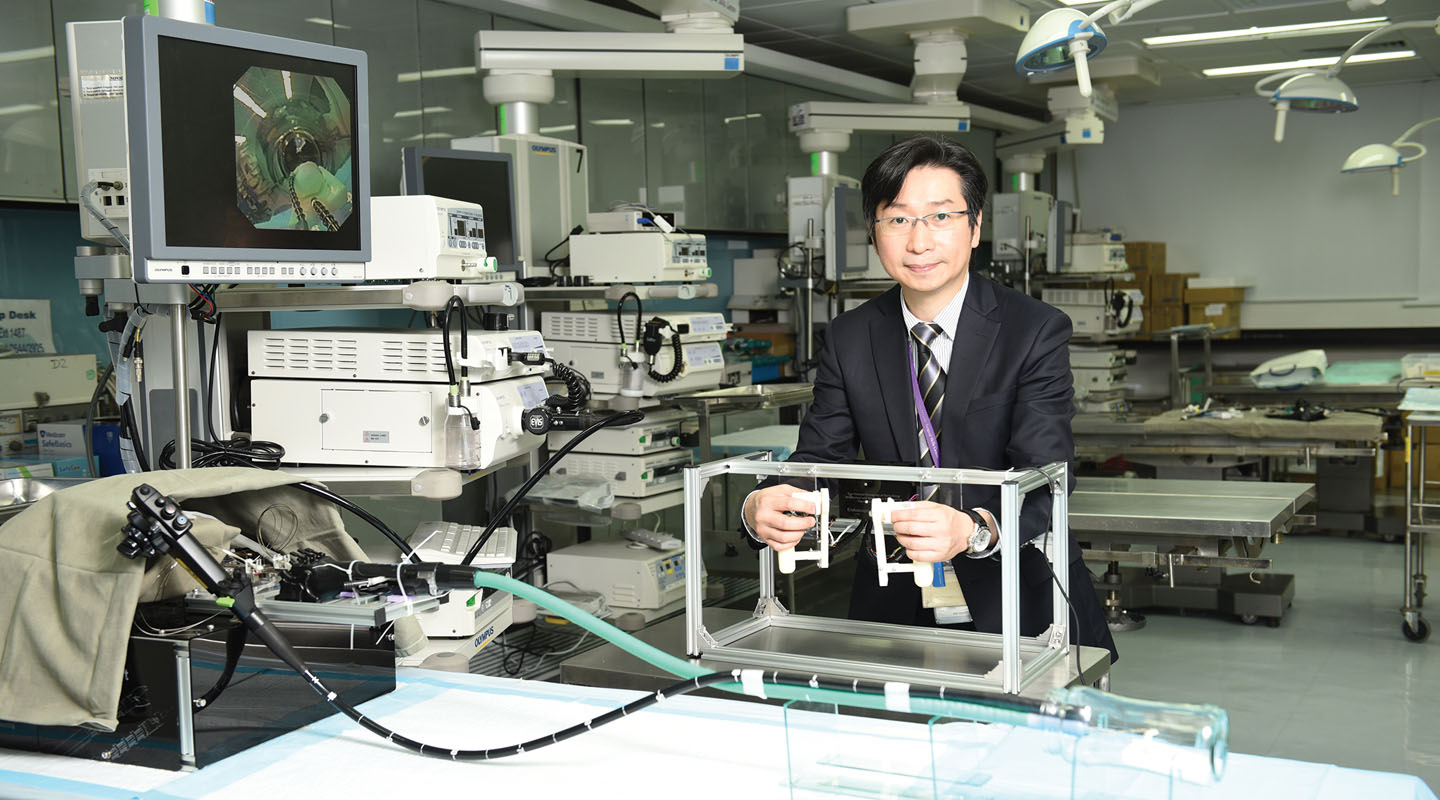

CUHK has been pushing the frontiers of minimally invasive surgery for a quarter century. A new centre on cutting-edge engineering and medical research is the latest testimony to the University’s commitment to medical innovations.

Twenty-five years ago, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) was rarely heard of in Hong Kong. It was not until 1990 that Prof. Chung Sheung-chee Sydney, former Dean of Medicine at CUHK, introduced the then novel surgical technology to the Prince of Wales Hospital and performed the first laparoscopic gallbladder removal surgery. It has since blazed the trail for MIS in the territory.

In 2005, the CUHK Jockey Club Minimally Invasive Surgical Skills Centre (MISSC) was established as a platform to provide training and practising opportunities to surgeons in and outside Hong Kong. Today, most operations can be carried out in the form of MIS.

What is minimally invasive surgery? Prof. Philip Chiu, director of MISSC, said, ‘There is no objective definition of MIS, but its primary aim is to minimize the size of incisions, to reduce trauma and pain suffered by patients, to enable faster recovery, and to lower the cost of surgical procedures and aftercare.

‘MIS has reached a new height—non-invasive surgery, which is performed through the body’s orifices such as the mouth, nose or anus.’

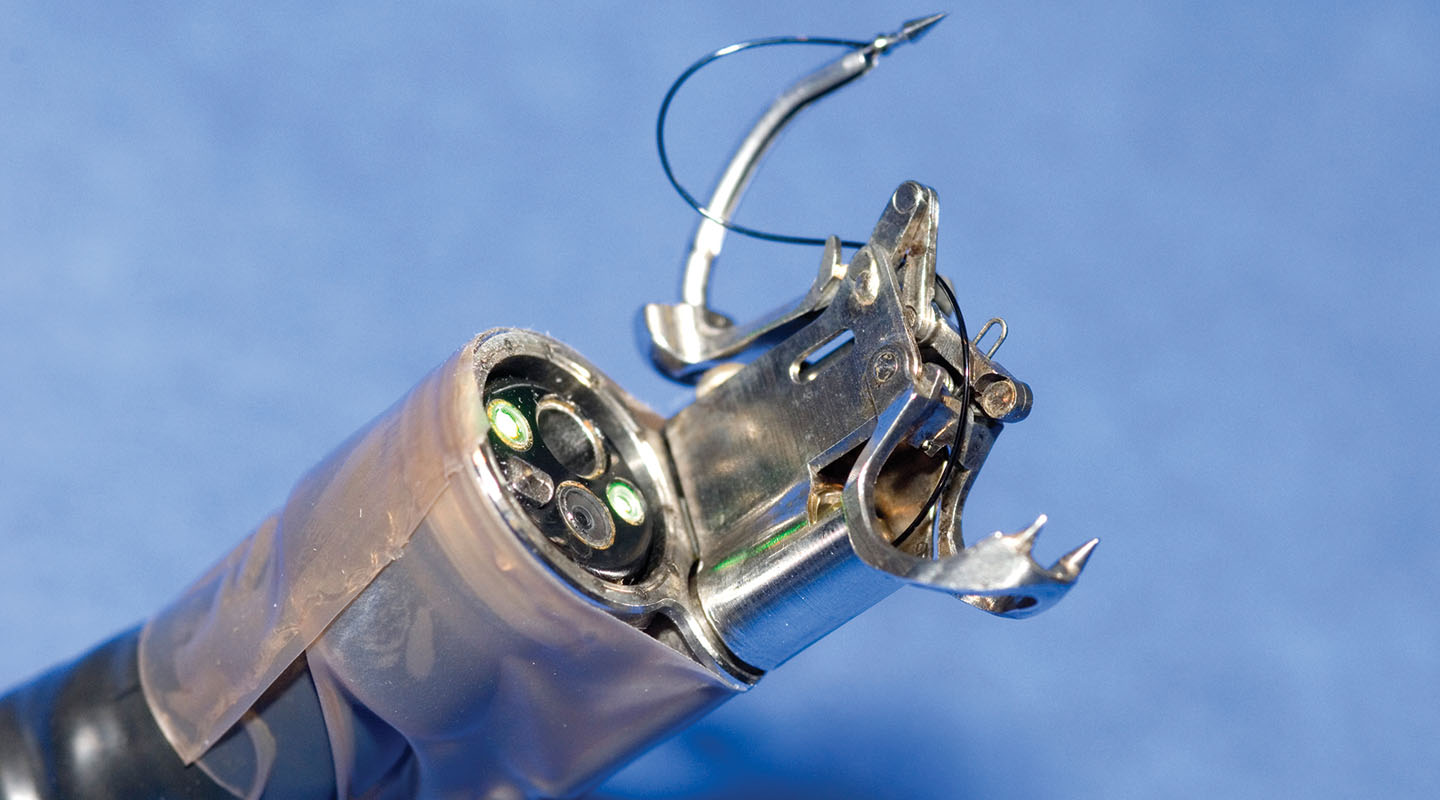

Professor Chiu took the endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) he introduced to Hong Kong in 2004 as an example. ‘Treating early bowel cancer used to involve removing the entire organ. In endoscopic surgery, doctors remove a tumour and infected tissues nearby through an endoscope which enters through the mouth. The organ remains intact and no incision is made. Patients can eat the day after the operation.’

But Professor Chiu pointed out that no break in the skin does not mean no wound at all. Patients go through a surgery nonetheless, be it minimally invasive, non-invasive, or conventional. It’s only how it’s done that is different.

The advent of MIS brings new opportunities as well as challenges for surgeons. By traditional apprenticeship training, surgeons were taught to operate directly with their eyes and hands. ‘See one, do one and teach one.’ Surgeons can directly put their hands into the patients’ bodies through big incisions. In emergency situations, they can immediately exercise manual skills to react and control, e.g., to stop bleeding by gently pressing the bleeding point.

To perform MIS is to look at a 2D screen to perform a 3D surgery. ‘It feels a bit like you are operating with your hands tied. But the advantage is that the laparoscope can take you to a close inspection of the affected area.’

Precision is crucial in performing MIS, so is pre-surgical training. ‘Surgeons go to classes to observe how operations are done, and to practise using computer simulation. They also have to practise basic surgical steps on animal models. When they are fully acquainted with the procedures and techniques, they are allowed to assist the chief surgeon to perform simple procedures in a surgery. Eventually they’d take charge of the whole surgery under the surveillance of their trainers.’

The MIS technique has been applied to gallstone removal, bowel cancer, gastric cancer, adrenal gland, liver, lung, and kidney. In 2005 the Department introduced the first da Vinci® S Surgical System in Hong Kong, followed by an updated version in 2008. The surgeon at his/her control console now sees a superior 3D high-definition image of the operating field. Last year, the Faculty of Medicine completed Asia’s first Gastric Pacemaker implant surgery for a patient suffering from gastroparesis.

‘Over the last 10 years, MISSC has trained over 15,000 health care professionals. About 70% are from Hong Kong, and the remaining 30% from the mainland, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, etc. The most iconic training programme is on robot-assisted surgical operation. In Asia, only Hong Kong, South Korea, and Japan offer such courses. In 2008, MISSC became Asia’s first accredited robotic surgery training centre,’ said Professor Chiu.

‘But we are not engineers,’ Professor Chiu said, ‘We don’t have any clue if any engineering innovation can be applied to medical treatment. That is why the University established the Chow Yuk Ho Technology Centre for Innovative Medicine earlier this year. I took up the role of its director. The centre is to bring engineering and medical research together for the benefit of the patients. It focuses on three research areas in biomedical engineering—robotics, imaging and biosensing, including nanorobotics, innovative neuro-imaging and non-invasive medical monitoring. We aim to transfer innovative technologies to the area of clinical equipment and practice, in order to enable a more effective and up-to-date treatment for patients in need.’

This article was originally published in No. 461, Newsletter in Aug 2015.