Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Pining in the Inner Chamber

The history of Chinese paintings has been illuminated by the presence of some talented women. But these female painters and their works must be viewed and understood in their historical and cultural contexts.

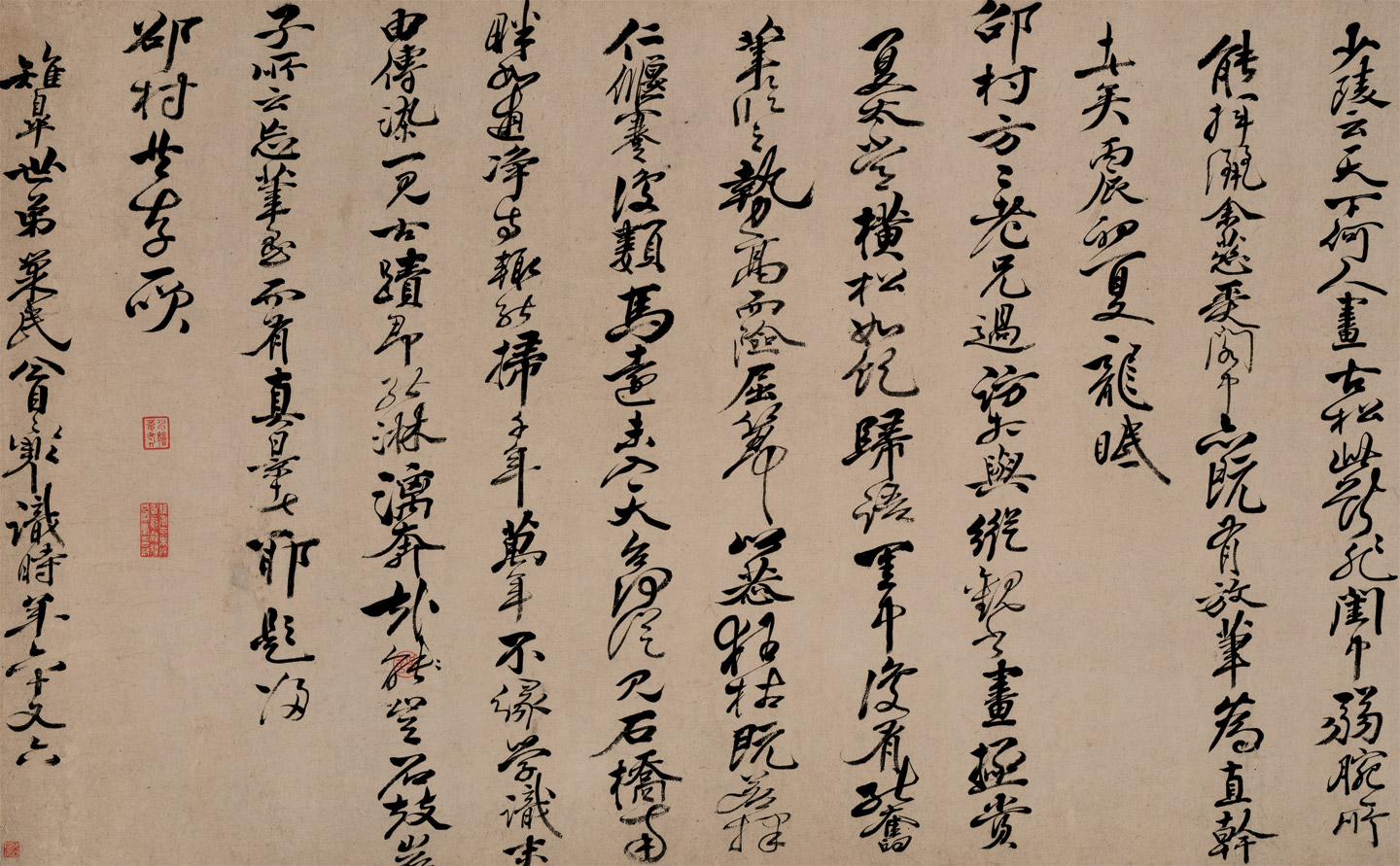

A few things can be learned from Pine Trees after Xia Chang, housed at the Art Museum of CUHK. The painting is attributed to Cai Han (1647–1686), a concubine of Mao Xiang (1611–1693), a famous literary figure and calligrapher in the Ming Dynasty.

First, the masterpieces by misses and madams would not have come down to us without male interventions. The social propriety in the Ming Dynasty prescribed that, without the support and endorsement of a male member of the family, a woman painter’s work could hardly be seen or circulated outside the family. In this case, the idea of the painting came from the patriarch Mao himself. After he had viewed a horizontal scroll of a dragon-like pine tree by Xia Chang (1388–1470) with his friend Fang Shaocun, Mao went home and described it to his family. In the inscription on the painting, Mao states:

And there the brush was pushed and the tree was imitated. The pine tree was lofty yet unconventional, twisted yet respectful, eccentric yet relaxed, and hunched and crouched to the idea of ren; (the style) is similar to Ma Yuan.

It was a common practice in the Ming period for husbands to inscribe on the paintings of their wives or concubines to authenticate the works as well as to provide justifications and endorsement for the circulation of them. For example, Ge Zhengqi (d. 1645) would inscribe on the paintings by his concubine, Li Yin (1616–1685) and Zhao Jun (d. 1640) would do the same on the paintings by his wife, Wen Chu (1595–1634). In this tribute to Xia Chang, the skill of Cai Han, if indeed she’s the painter, would be all the more amazing if she had not seen the scroll for herself but only relied on what another had at one remote described to her.

Second, while other female painters from this period would put their seals on their works and hence put the question of authorship beyond doubt, it is unclear who the real painter of Pine Tree after Xia Chang was. Mao’s inscription has not helped, either. He has explained the origin of the painting from viewing a similar one by Xia Chang with Fan Shaocun, even quoting Tu Fu and referring to Ma Yuan, but failed conscpicuously to name the presumably female painter from his inner chamber. Another concubine of Mao, Jin Yue, was also an accomplished painter. She and Cai Han were collectively known as the ‘two painters of the orchid chamber at Waterpaint Hermitage (Mao’s residence) of the Mao family at Zhigao’. There are no individual seals on the painting. There is one, however, bearing the double byline of ‘the two painters of the orchid chamber at Waterpaint Hermitage of the Mao family at Zhigao’. The painter could have been Cai Han or Jin Yue, or both.

Lastly, paintings by women painters were not only works executed during their leisure hours or purely for self-amusement purposes. Many were given away by their husbands to others to secure friendships or build social networks or in some cases even obtain financial benefits, as works by women painters were very much sought after in the art market and could often be exchanged for a high price. Records indicate that Ge Zhengqi often used Li Yin’s painting as gifts. The famous art critic, Li Rihua (1565–1635), recorded that Ge Zhengqi presented a painting by Li Yin to him and he was obliged to return the favour with a poem. Ge Zhengqi also recorded another incident in which Li Yin’s painting was presented as a gift to Chen Hanhui (1590–1646) in 1630. Wen Chu’s husband, Zhao Jun, presented her works to his friends and received monetary benefits in return. The ‘lofty yet unconventional, twisted yet respectful, eccentric yet relaxed’ pine tree was probably first shown to Fang Shaocun. Mao Xiang presented this painting by one or the other or both of his concubines to Fang Shaocun probably to secure and to commemorate their friendship.

This article was originally published in No. 492, Newsletter in Feb 2017.