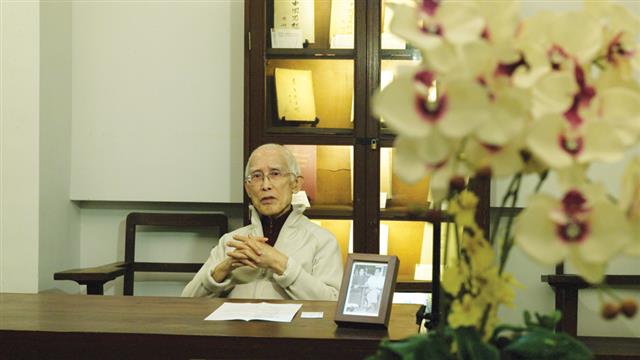

Poet, prose writer, translator,

Professsor, Dept. of Chinese

Language and Literature (1974–85)

Some comment that poetry is nothing more than prose in lines. How would you tell them what poetry is?

Many people who are not happy with modern Chinese poetry would say so. But looking back, classical Chinese poetry was not necessarily presented in lines. To think that a badly written piece of text can be disguised as a poem by splitting into lines is ridiculous. On the other hand, prose can also be poetic, like the first few four-character phrases in a famous letter (written by Qiu Chi, 463–508 A.D.). It's a poem by nature but was presented as prose. Interestingly enough, there are lines that fulfil the rigid form requirements of classical Chinese poetry, but lack the essential element of imagination. They have the body of a poem but no soul. The distinction is not simply in the appearance.

Is the popularity of the Internet and mobile phones advantageous or disadvantageous to literary creation and dissemination?

It depends on how you use the medium. The short message contest of Taiwan Mobile calls for creative and poetic messages of no more than 70 words. The message which won the first prize of NTD 70,000 was 'Dad, Happy Mother's Day!' Simple and short, it tells a story of a single-parent family in which the father also plays the motherly role. As one of the adjudicators, I have been invited to write some sample messages. One of them is written for a man to his girlfriend—'Buy no more LV (Louis Vuitton), for it's just half of LOVE.' Information technology creates platforms for literary writing. But if you just keep phubbing on your smartphone day after day, without paying attention to face-to-face interaction with people or the beautiful nature around you, what you can benefit at most is just a little convenience in communication.

Is the Chinese University a good place for poetry writing?

Needless to say, yes! No other activities can complement this ideal campus better than writing poetry. Everybody can do it, it doesn't matter whether you're studying Chinese, foreign languages, fine arts or even science and technology. I came from Taiwan to teach here for 11 years. My quarters faced Tai Po Road, with Pat Sin Range a little bit to the right, Plover Cove in the far horizon and Ma On Shan close by. That was fantastic! I wrote a lot of poems and prose, plus some academic papers and two translated books. Those were very productive years.

Would you tell us how you feel about the westernization of the Chinese language?

Some cases are successful. Xu Zhimo (Chinese poet, 1897–1931) has two famous lines about a romantic encounter, which literally read 'You have yours, I have my direction.' He could have written in a traditional Chinese way—'You have your direction. I have my direction.' But he avoided the repetition of the word 'direction' by adopting the omission allowed in English grammar as in 'You have your direction, I have mine.' This is a good attempt. As for unsuccessful cases of westernization, there are far too many in Taiwan and in Hong Kong. It's the worst in mainland China where people habitually add 'jinxing', which means 'to proceed with', before verbs and then nominalize the original verb, creating awkwardly redundant phrases in terms of Chinese grammar. For example, instead of saying 'We are talking' now, it will be 'We are proceeding with a talk'. Another example is 'zuochu'—'to do' as in 'to do a contribution' instead of 'to contribute', 'to do a decision' instead of 'to decide'. Such cases of westernization are undesirable.

Why is it like this? What can be done?

We have been using vernacular Chinese to write and to teach since the May Fourth Movement a century ago. We think that classical Chinese has been abandoned; in fact it has not. Some parts of it have been retained as idioms in our daily usage. Chinese idioms are tonally pleasant, syntactically balanced, and succinct. Sometimes we even sacrifice the internal logic of an idiom in order to maintain these qualities. For example, ´qiānjūn wànmǎ´—´a thousand soldiers and ten thousand horses'. It's illogical to have one soldier to 10 horses, but the combination of level and oblique tones make it sound right. Our daily conversation is decorated with lots of classical Chinese elements, it's a pity we don't pay much attention to it and seek to borrow ideas and usages from the English language. It's one of the factors leading to the abusive westernization of the Chinese language. I basically write in vernacular Chinese. But when it comes to crucial points, I would turn to classical Chinese, not only for variety, but also for the many good concepts and marvellous expressions which make my points more convincing.

As the number of classical Chinese essays dwindles in the secondary school Chinese Language curriculum, what can we do to enhance the Chinese language proficiency of our students?

Classical Chinese essays open the door to Chinese philosophies and history. The Cantonese dialect is rich in classical Chinese. I've heard many ancient and refine Cantonese expressions during my years in Hong Kong. The nine tones of Cantonese add wonders when you recite rhymed verses and proses written in classical Chinese. It's a pity if only a few pieces could be included in the textbook. When I was in secondary school, reading novels was my hobby. Novels like Three Kingdoms, The Water Margin and Journey to the West were written in a hybrid language of classical and vernacular Chinese. I think schools can at least try encouraging novel reading to enhance the students' knowledge in classical Chinese. In my school years, recitation was important. Modern education theories suggest that recitation would do harm to the development of school children. But in my school years, recitation was important. There is a saying that memorizing the Three Hundred Tang Poems would make you a copycat poet, if not an authentic one. It is because you would have a better grasp of what tonal beauty, couplets, formality and informality means. I remember there was an annual schools speech festival in Hong Kong. It’s nice if the festival could promote recitation of essays and poems.

What is the biggest change that you experience upon returning to CUHK?

I left CUHK about 30 years ago. But I have revisited the campus some 20 times since my departure, so I don't feel like a complete stranger here. That said, I noticed there are more buildings every time I come back. I guess the number has tripled. There were only three Colleges, now there are nine. The two water towers were the only tall buildings then, now there are plenty, and there are more staff now. The hostel I lived in has turned into a postgraduate student hostel. I am not allowed to go inside for a nostalgic tour. The diesel trains of the Kowloon–Canton Railway before would make a turn after reaching Cheung Shu Tan, and the sound of the engine would die off after that. Now we have electric trains, and the scene of hawkers carrying baskets of snacks, like chicken feet, can no longer be seen. CUHK students today are taller, stronger and better-looking than their predecessors, and they all look happy.