The True Cost of Fast Fashion

Once upon a time, there were two fashion seasons a year—spring/summer and autumn/winter; now fashion changes every week, thanks to fast fashion stores that keep churning out affordable apparel and bring catwalk styles to the public in a matter of weeks. Many of us are happy to pick up a HK$49.90 top, wear it once, and forget about it, but do we ever pause to think about what prices we are actually paying for fast fashion?

Today’s Treasure, Tomorrow’s Trash

The fashion industry by design is constantly changing with the seasons, but fast fashion can change weekly. It’s not uncommon for shoppers to wear an item once or twice before throwing it away for next week’s style, aided by the poor quality of many of the clothes causing them to fall apart after several washes.

According to new analyses of waste statistics by Greenpeace, Hongkongers send 110,000 tonnes of textiles to the landfills each year, meaning that on average they throw out around 1,400 T-shirts every minute. Per capita, it works out to about 15 kg of clothing disposed of in a year, the weight of roughly 102 T-shirts.

Dirty Business

Second to oil, textile is the most polluting industry in the world. Every stage in a garment’s life-cycle threatens our planet and its resources.

It can take more than 20,000 litres of water to produce 1 kg of cotton, equivalent to a single T-shirt and a pair of jeans. Up to 8,000 different synthetic chemicals are used to turn raw materials into clothes, including a range of dyeing and finishing processes. The relentless release of these chemicals into freshwater systems endangers the environmental health of surrounding communities.

Once manufactured, the garments are put in containers and sent by train or container ships, and eventually rail or trucks to the retailers. The carbon footprint of one T-shirt is estimated to be 15 kg. This means a T-shirt’s carbon footprint is approximately 20 times its own weight.

Who Made Our Clothes?

Keeping prices low requires fast fashion companies to manufacture in countries with low wages, where contractors and subcontractors need to meet requirements for low costs, often on the account of workers’ safety and working conditions.

In 2013, the Rana Plaza factory building collapsed in the city of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The building was unsound, and the safety of all its occupants was put at risk daily. In the end, 1,134 people died and over 2,500 were injured in the name of fast fashion.

A Thread of Hope

Although fashion and sustainability may seem like worlds apart, there are brave players in the fashion industry who are introducing sustainable habits and resource optimization that have the planet’s best interest in mind. Derek Chan, for example, is an indigenous designer and founded his menswear label DEMO. in 2012. Its eco-friendliness is manifested in the use of diversified textiles.

‘Cotton and polyester are the world’s most commonly used fibres. Polyester, being a synthetic fiber, depends heavily on coal and petroleum. Cotton, albeit natural, leaves gigantic water and carbon footprint in its planting and manufacturing process. Therefore, when I source fabrics for a new collection, I try to blend in other kinds of fibres, such as tencel and linen, to lessen the environmental footprint of the final garment,’ explained Derek.

Aside from 'DEMO.', Derek is also working on his M.Phil degree in fashion at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, his research topic being biodegradable fabrics grown from bacteria. ‘If it proves successful, I will use this technology to manufacture my company’s clothes, bags, and accessories, which will be grown directly from the bacterial ingredients without the knitting and weaving processes.’

A Changing Trend

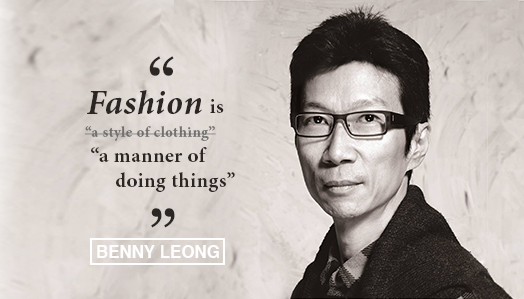

Benny Leong, assistant professor of PolyU School of Design, predicted that digital production would be a model of sustainable fashion in the near future: ‘Think about how digital weaving, printing and 3D printing could revolutionize the way fashion is perceived and consumed. Not only would it realize a truly “local-for-local” production-consumption cycle, but also closed-loop recycling of materials.

‘In fact, such practice is not that far from reality. A Hong Kong based company TPASSION has been producing garments and T-shirts by employing local skilled workers and fashion, graphic designers, using natural dyed organic cotton and eco digital printing technology.’

But Professor Leong added that the new model does only half the job for bringing about positive changes in the clothing industry. The other half relies on us—the consumers. ‘If our desire to be seen as fashionable through constant redressing our body remains unchanged, there will never be a sustainable future for us and the generations that follow. So, instead of interpreting fashion as “a style of clothing”, could we view it more as “a manner of doing things”? ’