Melting Glaciers in High Asia and their Impacts on Water Sustainability

Prof. Liu Lin

Earth System Science Programme

High mountains spanning Himalaya, Hindu Kush, Karokoram, Tibet, and Tien Shan are Asia’s water towers. More than 1.4 billion people depend on water originating from these areas and flowing through major rivers. As climate is changing in these areas, many glaciers are melting at accelerated rates. What are the impacts of melting glaciers on water supply downstream? The short answer is: there are both good news and bad news; and more bad news for our children and grandchildren.

Overall, water from Asia’s major rivers such as the Yellow, Yangtze, Indus, and Ganges are mainly supplied by snow melt and precipitation. Melt water from glaciers only acts as a supplementary source, contributing about 10% of the total runoff. Glaciers are more like an ‘emergency fund’ of water, playing a buffering role every year when the saving account is draining down. Imaging on a scorching summer day, snow is far-gone and the raining season is yet to come; it is the melting water from glaciers that keeps feeding streams and rivers and recharging groundwater aquifers.

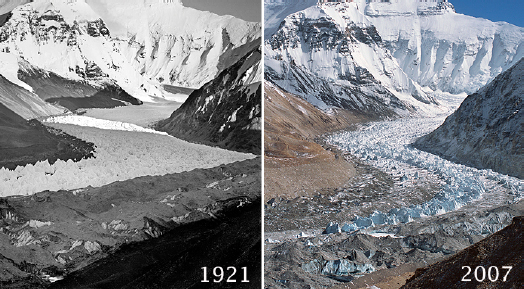

Accumulating scientific evidences from ground and space observations have found that most glaciers in high-mountain Asia are getting shorter, smaller, and lighter, although scientists are still debating about the rate of ice mass loss, ranging from 4 gigatonnes per year to 47 gigatonnes per year (1 gigatone is 1,000,000,000 metric tonnes; 1 cubic meter of water weighs about 1 metric tonne).

In short term, this actually means more water supply downstream as we are withdrawing from this emergency fund. A group of European scientists predict a continuous increase of river runoff at least until 2050 in most of the river basins in Asia. This will be beneficiary for people living in regions with scarce water resources. But increasing runoff also means an increased risk of flooding during the peak melting season.

But what will happen after the emergency fund has run out against the backdrop of long-term ‘economic recession’, namely global warming? We will lose the natural buffer and therefore be more vulnerable to the natural seasonal shortage of water supply, especially as the monsoon-driver precipitation is predicted to decline.

Since this short-term increase of water supply from melting glaciers is not sustainable, science-based policy making and water management are greatly desirable to cope with the shifts in water availability and long-term loss of glacier water. It is not a trivial task given the complex natural systems, the complicated social systems across multiple countries and cultures, the diverse patterns of water use, and the geopolitical conflicts in the region. As science is making advancement in the understanding of the natural systems, it is the governments’ roles to take immediate and collaborative actions to implement climate change policies. We should watch closely if any universal agreement on climate change can be achieved at the upcoming 2015 Paris Climate Conference (COP21).