A Watery Future for Our Cities

In August 2016, prolonged rainfall in southern parts of the state of Louisiana in the US resulted in catastrophic flooding that killed 13 people, displaced 30,000, and damaged tens of thousands of homes and businesses. Two months before the Louisiana floods, after days of torrential downpours, the Seine, which runs through Paris in France, rose five metres above normal levels in June and burst its banks in places, forcing the Louvre, the world’s most visited museum, to close.

Climate Change’s Fingerprint in Flooding

In the historic rainfall that caused catastrophic flooding in Louisiana, the state was pummelled by some 7.1 trillion gallons of water in the span of seven days during what was called a ‘1-in-1,000-year event’. Scientists believed that an extreme rainfall event like this is now expected to occur at least 40% more often than it was in our pre-industrial past because of climate change.

Prof. Chen Yongqin David of the Department of Geography and Resource Management, CUHK, said, ‘The three most certain consequences of global warming are rising temperature, sea level rise and more extreme weather and climate events. In one way or another, they all contribute to the intensification of the global “water engine” driven by hydrologic cycle and the increasing magnitude and frequency of flooding around the world.’ According to NASA, the average temperature in the first six months of 2016 was 1.3°C warmer than the pre-industrial era level. A warming atmosphere and oceans should lead to more intense and frequent rainstorms, because warm weather leads more water to evaporate forming wetter clouds.

The Ocean Pushes Back

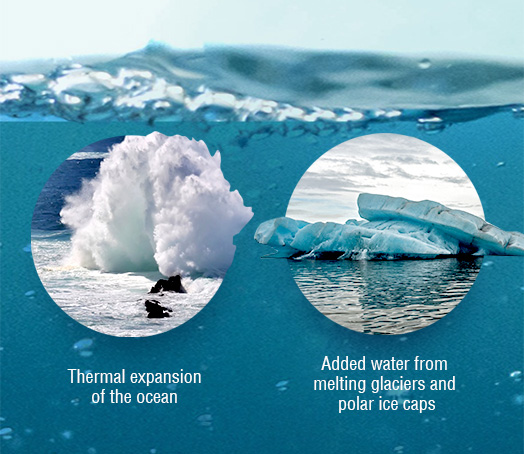

Over the past century, global sea levels have risen by 10 to 20 cm. However, the annual rate of rise over the past 20 years has been 3.2 mm a year, roughly twice the average speed of the preceding 80 years. Sea-level rise is caused by two factors related to global warming—thermal expansion of the ocean (as sea water warms, it rises) and added water from melting glaciers and polar ice caps.

In the US coastal cities along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts like Miami Beach, scenes of residents and tourists splashing across the sidewalk in ankle-deep water become increasingly commonplace. Known as sunny-day flooding, this fairly new phenomenon happens during the highest tides. Drains built to channel water to the ocean function in reverse as the ocean pushes back, becoming the conduits through which seawater surges inward, inundating the low-lying neighbourhoods of these cities. As a result, in places like Norfolk in Virginia, huge vertical rulers were erected beside low-lying sections of their roads, helping drivers to judge if floodwater swarming the roads is too deep to drive through.

Nations to be Lost to Rising Waters

The abovementioned US coastal cities are not the only victims of rising sea levels. Many low-lying nations such as the Maldives and Bangladesh face a similar or worse fate. The Maldives will lose some 77% of its land area by 2100 if sea level rises on the order of half a metre. In the worst-case scenario, the nation could be almost completely under water by about 2085 if sea level rises by one metre.

Bangladesh is also a potential hotspot threatened by rising sea levels. With about 80% of its territory being flatlands, and 20% of the land is one metre or less above sea level, a one-metre rise in sea level, one of several scenarios forecasted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), could inundate some 17% of the country’s land mass.

Will Hong Kong be Spared?

‘Over the years, thanks to the enormous efforts of and investments by our Drainage Services Department and other stakeholders, flooding risks in Hong Kong have been substantially reduced as evidenced by the huge drop in the number of flooding blackspots from 90 in 1995 to 8 this year,’ said Professor Chen. Hong Kong last witnessed significant flooding in 2008, when storm surges induced by Typhoon Hagupit caused major flooding in many parts of the territory, including the seaside village of Tai O.

With its hilly and mountainous terrain, Hong Kong will not be totally submerged by sea water despite the threats of rising sea level. But Professor Chen said, ‘We do have a lot of low-lying flatlands which have been largely developed for residential and commercial uses. It is imperative for our government and scientists to study how climate change may increase the flooding risks at different locations in Hong Kong and take these factors into consideration as adaptation measures in our urban planning and design, particularly in the design and construction of our infrastructure such as land reclamation, housing development, stormwater management and flood prevention facilities, and transport system.’

Getting Prepared for Mother Nature’s Challenge

To get to the root of the matter, it is important to achieve the objective of the Paris Agreement hammered out by nearly 200 countries in December 2015, which calls for the world ‘to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels’.

The most effective way to slow global warming is to slash the greenhouse gas emissions that drive it. The IPCC projections forecast a sea-level rise of 52–98 cm by 2100 if greenhouse emissions continue to grow, or of 28–61 cm if emissions are strongly curbed. China and the US, the world’s biggest emitters of greenhouse gases, have announced in September that they would formally ratify the Paris Agreement, which was a significant advance in our battle against global warming and rising sea levels.