Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Ho Puay-peng on Tsz Shan Monastery—Spirituality, Antiquity and Modernity

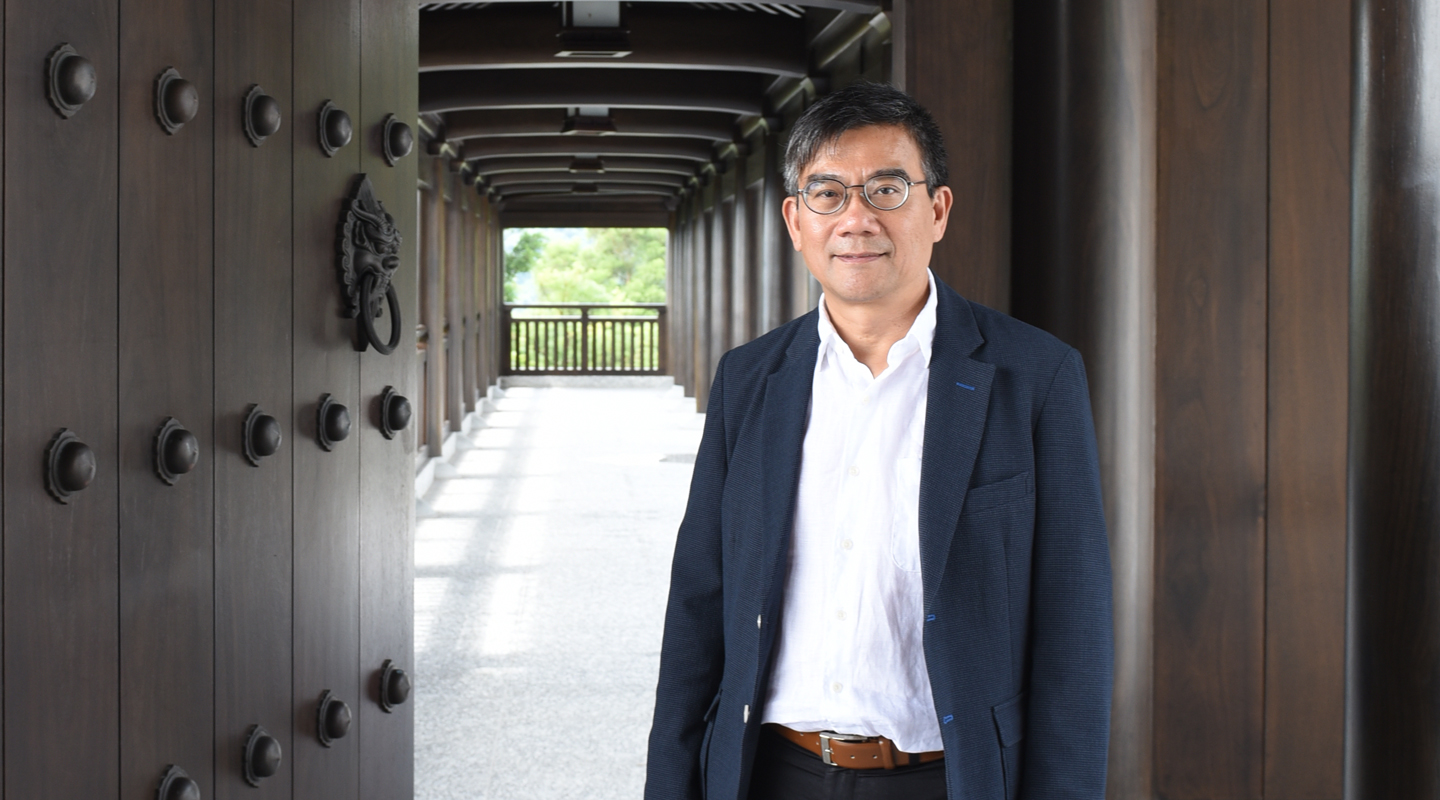

Architecture professor Ho Puay-peng talks about how the Tsz Shan Monastery re-interprets traditional Buddhist art for a modern sentimentality.

Ever since a few years ago, you’ll see an immense statue of Guanyin, the Goddess of Compassion, if you look towards Tai Po from the CUHK campus. Elegantly robed in white, holding the Pearl of Wisdom and a vase of sacred water, she gazes graciously at the sentient beings below her. But it is only recently that this 76-metre tall Guanyin can be viewed up close. The statue stands in the 46,450 m2 compound of Tsz Shan Monastery which opened its doors to the public a few months ago.

The project’s chief architectural consultant is Prof. Ho Puay-peng, CUHK professor of architecture. Commissioned by Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing, it took 12 years and HK$1.5 billion to complete. The result is a tradition-inspired modern monastery that exudes pervasive spirituality.

Antiquity-inspired Modernity

In an age when ‘tradition’ and ‘modern’ have liberal interpretations, a tradition-inspired modern monastery can be anything from kitsch to a faithful replica of an ancient structure. Where in the spectrum does Tsz Shan fall? Deciding that and conducting the exhaustive research that entailed were important components of the project; they were also why Professor Ho, an expert in Buddhist architecture, was recruited.

‘It would be easiest to make a replica of Tang architecture,’ he observes. ‘It’s more difficult to build something that evokes both tradition and modernity. The process of research, full-size testing, and trial was a long one. This monastery is not an authentic replica of a Tang-dynasty Buddhist monastery, but a research-based interpretation suitable for modernity. Put simply, the construction is modern in the inside and traditional on the outside. The monastery’s skeleton is made of steel and it was erected by builders using contemporary methods.’

The Spiritual Element

While monastic architecture from the Tang, Northern Song and Liao/Jin dynasties might have been one point of departure for the layout and physical design, there’s also the spiritual dimension to consider. A religious building ought to impart a religious atmosphere, and offer believers an authentic experience. Through studies on how Buddhist doctrines can be expressed through the sequencing of images and spaces, and the relationship between descriptions in Buddhist texts and structures of the time, Professor Ho and his team of CUHK doctoral students came up with concepts that would instil a spiritual feeling in the physical environment. ‘I feel there should be completeness and consolidation, a harmonized entity from which the presence of Buddhist doctrines is felt. This is one of the more important precepts of Tiantai Buddhism, a leading school of Chinese Buddhism during the Tang and Song dynasties. “Yuanrong” (圓融) is about consolidating different things to produce a new and perfect entity,’ explains Professor Ho.

The compound has two axes—one leading to Guanyin, one to the Buddha in the Main Hall. The central axis, originating in the harbour, guides visitors to the nucleus of the monastery. The second axis runs diagonally down from the hill past the Guanyin statue. They meet in the courtyard near the Sanmen or the Gate of the Three Liberations. This also illustrates the concept of a harmonious whole. ‘The religious images are not manifested at first sight. In a church, we see the crucifix right away but in Buddhist architecture, you need to go through spaces imbued with meaning in order to see Guanyin or Buddha,’ Professor Ho points out.

Modern Accents

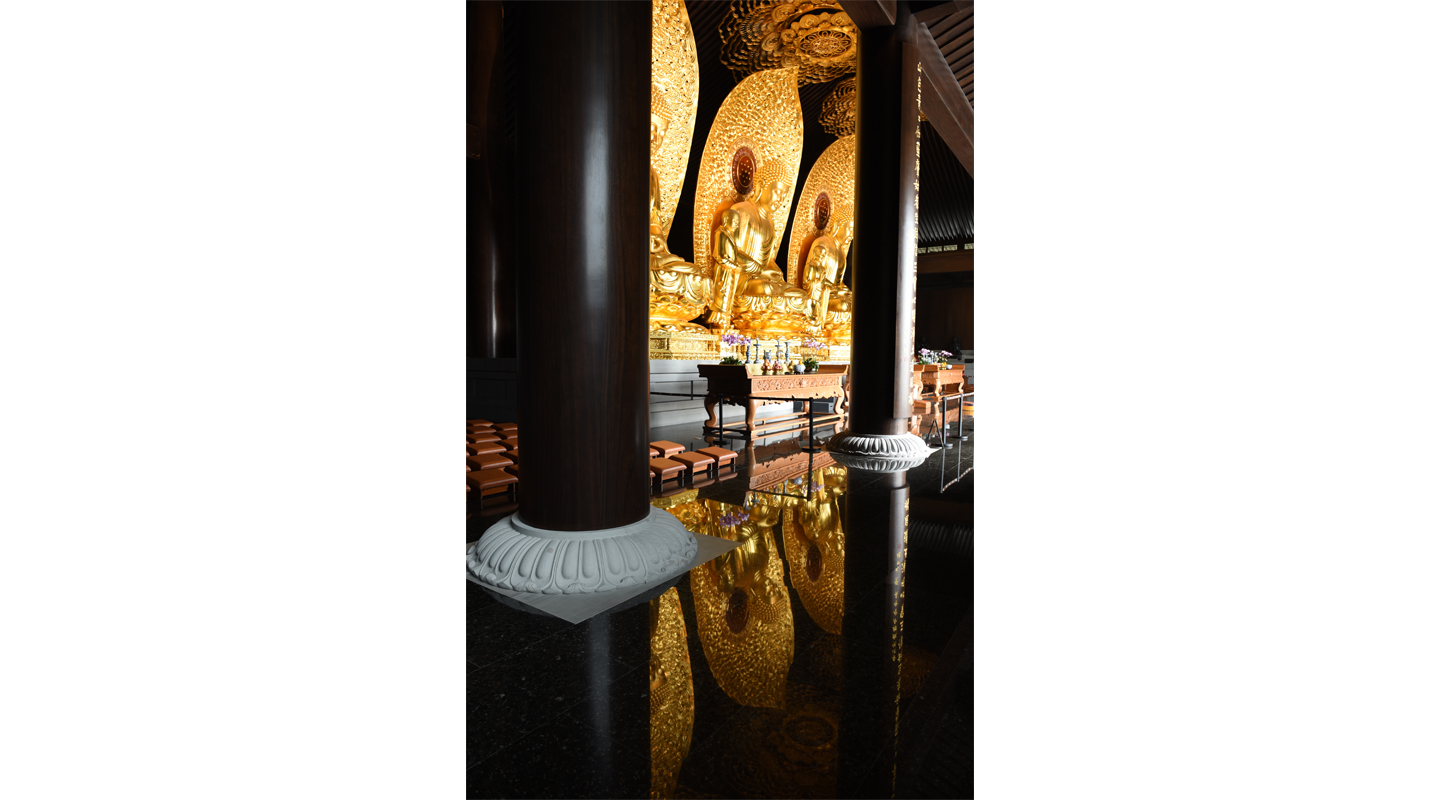

The monastery’s steel structure is encased in African zitan wood, which is dark brown with a graceful antique look. In some cases, like in the bases of pillars, the steel is encased in stone. There is no need for supporting pillars in interior spaces; the only ones you see (in the Main Hall) are there to create an ambience. Neither are there interlocking brackets under the eaves, that are a prevalent feature of Tang architecture. ‘When light streams from under the eaves at night, the roof seems to float above the hall,’ Professor Ho observes. The monastery has a palette of dark brown and silvery grey (flooring, roofs), accented by the green of nature. The cleaner lines and minimalist palette lend the monastery modern touches that complement Tang aesthetics very well.

Referencing China’s Buddhist Heritage

The design references Buddhist architecture and iconography in China from the 9th to the 12th centuries, including structures that no longer exist. The bronze-forged steel Guanyin statue, twice the height of Lantau Island’s Big Buddha, honours the tradition of the colossal images that first appeared in the Yungang Grottoes in Datong, Shanxi, and the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. ‘Sheer scale was used to express compassion and to allow the icons to touch on lives far and near,’ Professor Ho observes.

The monastery has balmy corridors overlooking the harbour. ‘Monastic corridors are quasi-enclosed spaces that are mainly used for rituals. Fashionable in 9th and 10th century China, they are a rare feature nowadays because they’re expensive to make. The ones at Tsz Shan share features with the 7th century Hōryūji Temple in Nara.’

The Maitreya Hall sees a statue of the Buddha Maitreya flanked by the decoratively painted Four Heavenly Kings—all sculpted on camphor wood. Decorative painting was traditionally used on wooden and clay sculptures. The Buddha is painted gold, which, for a modern twist, is matt on the body, and glossy on the robe and halo.

The larger Main Hall impresses with its sense of monumentality. Here are three statues in gold, again representing the concept of harmonious consolidation—the Great Medicine Master of the East, Amitābha Buddha of the West, and Śākyamuni Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. Above their heads, canopies feature innovative interpretations of patterns found in Dunhuang canopies. Intricately carved and glittering, they play off against the ceiling’s brooding solidity in a way that pleases the contemporary eye.

The back wall has a replica of a wall painting found in the Yulin Caves, 100 km east of Dunhuang, that are known for wall paintings dating from the Tang to the Yuan dynasties. The replica was produced by outputting images of the original painting on silk-like fabric from Germany. If you look hard at the high-resolution images, you might see the pixels.

The monastery also has a Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Hall, a Bell Tower, a Drum Tower, and a Library of Buddhist Texts. In a corner of a courtyard, a pond with water lilies and lotus sits. The lotus is a symbol for the Pure Land, and as such, is regarded by Buddhism as a conduit for rebirth. Rebirth comes in various forms—renewal of consciousness, reincarnation, or a physical coming into being. The last is exemplified by the monastery which is sprawled on a lush hillside once devastated by fire. ‘Tsz Shan’ literally means ‘Benevolent Hill’.

This article was originally published in No. 465, Newsletter in Oct 2015.