Prof. Li Hon-lam is the only member in the planning committee of the newly established CUHK Centre for Bioethics who is not from the medical or biological fields. He is a professor in the Department of Philosophy of CUHK and specializes in practical ethics. He believes that philosophical examination of issues of public concern (whether abortion, euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide, etc., are morally permissible) can lead to their clarification and resolution.

Professor Li explains his areas of inquiry with a few dilemmas and the Doctrine of Double Effect.

The Transplant Case

Suppose a doctor has five patients, each with failure of a different organ. She can save them by killing a healthy person who came in for a regular checkup, and transplanting his organs to her five patients. Most people would think that it is wrong to kill the innocent person in order to save the five patients.

Now suppose we can save either five strangers in Place A or one in Place B, but not all. Most people would think that we should save the five strangers in Place A instead of the one in Place B.

What accounts for these apparently different conclusions? The Doctrine of Double Effect states that there is a moral difference between directly intended harm and harm that is merely foreseen. In the above case, killing an innocent person for his organs is a directly intended harm and therefore morally reprehensible, whereas not saving the stranger in Place B (while saving five in Place A) constitutes harm that is merely foreseen.

The Doctrine also requires that the bad effect (or harm) must not be the means by which to achieve the good effect. That is, I cannot take a stranger's kidney by force in order to save my friend, even though I do not intend the stranger's death. That is because the harm (taking away someone's kidney) is the means to achieving the supposedly good effect of saving another human being.

Furthermore, the Doctrine requires that the good effect achieved should neutralize or even outweigh the bad effect indirectly caused (or foreseen).

The Doctrine goes back a long way and has its origin in the Roman Catholic Church which had relied on it to justify its view that craniotomy—whereby the head of the fetus is crushed in order to save the mother's life—is impermissible, because this would involve intentional killing. On the other hand, the Church had permitted hysterectomy, where a pregnant mother's uterus is cancerous and must be removed if she is to be saved, even if the fetus will be killed along the way.

The Doctrine is, however, untenable. Suppose a surgeon can save five patients but in the process must generate lethal fumes, which will seep into the room next door and kill the patient there (who for some reason cannot be removed). Although the Doctrine would justify this operation, moral philosophers generally believe that the Doctrine gives the wrong answer in this case.

The Trolley Problem

A related problem has attracted quite a bit of enthusiasm among academic philosophers lately. It goes like this: you are driving a trolley. Some terrorists have tied five innocent people to the track ahead. The brakes have been sabotaged so that you have no way of stopping the trolley. You would run over the five people if you do nothing. The only possible way out is to turn right onto a sidetrack where only one person is tied to the track. Should you turn right, or let the trolley run straight ahead?

Almost everyone (supporter of the Doctrine of Double Effect included) would say that it is morally permissible to turn right.

What if, instead of making a turn to the right, the terrorists gave you the alternative of pushing a fat man in front of the trolley in order to have it stopped in time so that the five people will not be hit (whereas the fat man will be killed)? This is sometimes known as the Fat Man Problem. Equally abominable it seems, but some people may think that steering the trolley right is more permissible than pushing a man in the flesh next to you. It is thought that you are ‘using' the fat man.

The Loop Case

Further consider this: if you turn right onto the man on the sidetrack, the trolley will run over him, but (in this version of the example) it will come back in a loop that will run over the five people on the main track. However, if you control the steering in a certain way, then upon impact the trolley will sink into the man on the sidetrack, thereby coming to a stop. You would be ‘using' him as a stopper, in the same sense that you had used the fat man in the previous scenario. Yet stopping the trolley this way seems to be more permissible than pushing the fat man. Why?

Professor Li looks at these cases this way: it is impermissible to kill the healthy patient in the Transplant Case. To kill him without his consent would violate his right to life. And there might be a more just solution: the five patients with organ failure can agree (say, by drawing lots) who should give up treatment and donate his good organs to the other four patients.

In the Fat Man Problem and the Loop Case, Professor Li thinks that there is a moral difference between using someone (the fat man) impermissibly, and using someone (the man on the sidetrack who would prove to be a stopper) permissibly. One might argue that the man on the sidetrack would die anyway. Whether the trolley sinks into him or not is therefore morally irrelevant. But if we push the fat man, we would be violating his right to life.

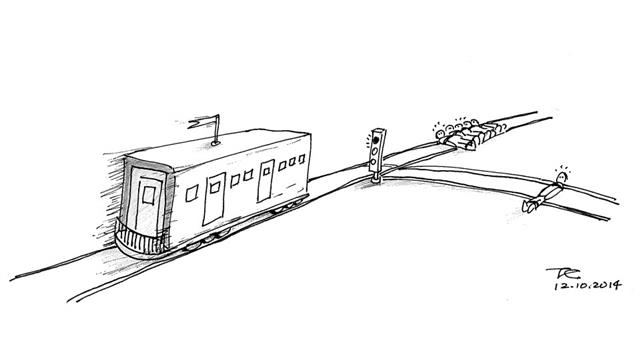

The Crisscross Problem

Finally, Professor Li offers a variant of the Trolley Problem: at a crisscross, the driver of the runaway trolley must turn either left or right. Turning left would hit five people, whereas turning right would hit only one. The consequences would be the same as in the Trolley Problem, but the choice is more obvious as averting a crash on five (the good effect) outweighs, arithmetically at least, squashing one (the bad effect). If one can argue that inertia, or doing nothing, on the part of the driver (in the Trolley Problem) is not morally valuable, the Trolley and Crisscross Problems would look alike, and consequently the drivers in both cases should turn right.

It is finding and comparing answers to these questions that exercises a philosopher's mind such as Professor Li's for the investigations undertaken at the Centre for Bioethics from a philosophical perspective.

|

Prof. Li Hon-lam's bio Prof. Li Hon Lam studied philosophy at Princeton, jurisprudence at Oxford, and got his PhD in philosophy from Cornell. He had studied under Thomas Nagel and T. M. Scanlon, two of the most highly regarded and influential contemporary philosophers. Prior to embarking on an academic career, he had practised as a barrister-at-law in Hong Kong for three years doing mostly criminal cases. His research interests are in practical ethics, ethics, political philosophy and philosophy of law. |