Before joining CUHK as the associate director of the Art Museum, Prof. Josh Yiu had been a curator of Chinese art at the Seattle Art Museum for eight years. In late 2014, the Art Conservation Project of the Bank of America Merrill Lynch got hold of him through a mutual acquaintance, the chief conservator of the Seattle Art Museum, to consult Yiu about potential art repair projects in Hong Kong that were worth funding. 'That was during the same time when CUHK was holding the exhibition "Two Masters, Two Generations, and One Vision for Modern Chinese Painting: Paintings by Gao Jianfu (1879–1951) and Lui Shou-kwan (1919–1975) in the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford", and the Lui's family were considering donating some masterpieces. When the bank learned about the significance of Lui's paintings to Hong Kong, they decided to offer support,' said Professor Yiu.

Two Palms, Ten Fingers, One Brain

The restoration project takes place in the mounting studio in the annex of the Art Museum, where senior conservator Master Xie Guanghan will remount the 30 scroll paintings by Lui. Master Xie comes from Suzhou, a city in Eastern China adjacent to Shanghai. His father, Xie Genbao, was a far-famed scroll mounter and known as the maestro of Suzhou-style mounting. His expertise was passed down to his five children.

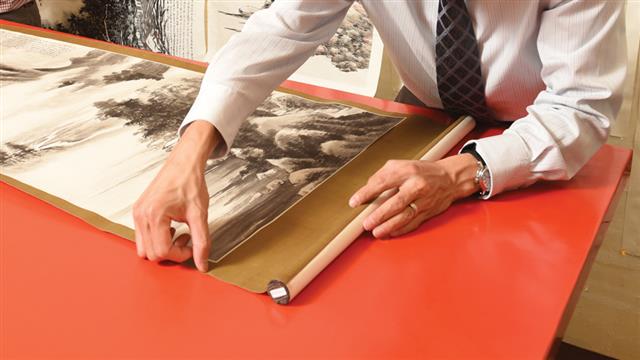

The mounting studio stood close to 5m high. Sunlight fell on a giant red-lacquer table over 3m long through 20 windows to the right. 'Conservators are highly sensitive to colour. The white we thought we knew has hundreds of shades to them. Under poor lighting conditions, their ability to perceive true colours can be affected,' said Professor Yiu. As for the red table, Master Xie explained, 'On one hand it is because red is an up-lifting colour. It boosts the spirit of the mounter. On the other, a red background helps to show the other colours placed on top. Black, white or green can be viewed clearly.' When asked what else is essential to a mounting room, he replied, 'Other than the necessary tools, a mounter relies mostly on his palms, his 10 fingers, and his brain.'

Removing the Old Mount

Remounting a hanging scroll starts with cutting away the borders to detach the painting core. Filmy as the core may seem, it consists of four layers of rice paper—the painting itself, the 'life paper' that is directly attached to the painting to increase its life span, and the double-layered backing paper.

Next, peel off the backing paper until the last snippet is removed. This process involves washing the core in warm water. After a night of wet treatment, the paste between the layers begins to lose its adhesiveness. 'The removal of backing paper is the most nerve-wracking for every mounter. During the process, the "life paper" will also be taken away. If 99% of it is off, the remaining 1% is not hard to clear away. But if 20% is left all over the back of the painting, it will be painstaking,' said Professor Yiu.

Master Xie added that the skills in removing 'life paper' include rubbing, nipping, and stretching. If your fingers are not deft enough, you are likely to puncture the painting. 'It takes more than a year or two to develop this kind of sensitivity. Also, no two paintings share the same remounting process. That's the reason why major collectors would never dream of handing over their artwork to a conservator-in-training.'

Remounting

Professor Yiu likened the washing and stripping of the painting core to the bathing process. The next step is to put fresh clothes on it. First, apply a new layer of 'life paper'. Second, prepare new borders. Every scroll painting has four of them—the left, the right, the top, and the bottom. A mediocre mounter will simply adhere four rectangular fabrics to the painting's edges, which will leave lines of joint on the surface. By Master Xie's standard, he makes borders out of a full-size piece of silk, in the middle of which he opens a hole where the painting core is placed. Lastly, turn the piece with its new borders face down on the table, and attach backing paper to provide extra strength.

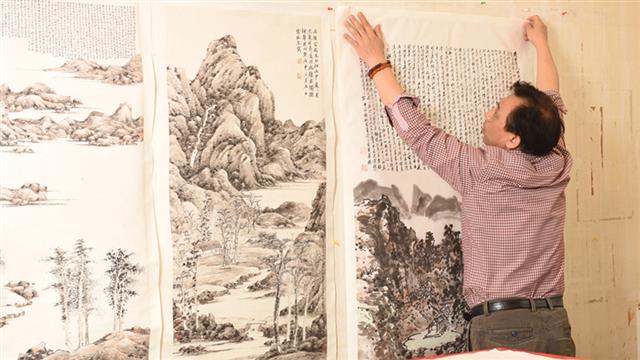

The scroll mounter used Lui's Mountains in the Rain to demonstrate how to choose the colour of the silk borders. 'Before mounting, the painting gives one an expansive feel of space. But it was mounted with Japanese-style dark green fabrics, which went against the painting's general appearance. Professor Yiu added, 'It's probably not the fault of the former mounter or user, because the scroll might be meant for hanging in a study, and thus mounted by the standard of a small room. To restore a masterpiece is to review its original style in order to revive the impression of space.' There they came up with an initial solution: replace with silk borders in light beige, and widen the top and bottom borders.

Suzhou-style Mounting

When talking about the characteristics of Suzhou-style mounting, the inheritor of the tradition summarized four points—careful choice of material, elegant colour combination, meticulous craftsmanship, and straight and smooth finish. 'The North is trying to mimic the craft of Suzhou. But their use of colours is not always the same. Buildings up north are usually grand and have a preference for navy blue and golden. In contrast, my home town is a dainty place for scholars and literati, where furniture and decorations are given a subtle touch.'

Professor Yiu added, 'The difference between remounting a work in three months and one is probably unknown to us. Except for Master Xie, the only person in the world who can tell the difference is the next conservator in six or 10 decades. No matter how well the painting is taken care of and how properly the museum is equipped, the day will come when the artwork needs to be repaired again. Master Xie is working for that day, so that the future mounter can take off with ease the lining papers he is making now. Conservators are unsung heroes in a true sense.'

To preserve the works of the influential Hong Kong painter Lui Shou-kwan is tantamount to protecting the city's artistic heritage. A restoration project as such requires a combination of resources, planning, and know-how. The Art Museum is fortunate to own them all.