Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Only Connect

Chan Sun-on’s quest for unity in science, education and life

Holding out his arm, with which he has dissected countless bodies over the last three decades, the home-grown CUHK anatomist gestured at his own blood vessels. After all these years, he still could not help but marvel at the makeup of the human body, the way life is so elegantly organized.

‘There are the arteries sending blood to the organs and the veins taking it out. Then there are the nerves controlling the organs and the lymph carrying waste away.’ A Christian as well as a scientist, he spoke with an almost religious awe of the various body systems being all in place, balanced, working in harmony.

‘It’s wonderful, isn’t it?’

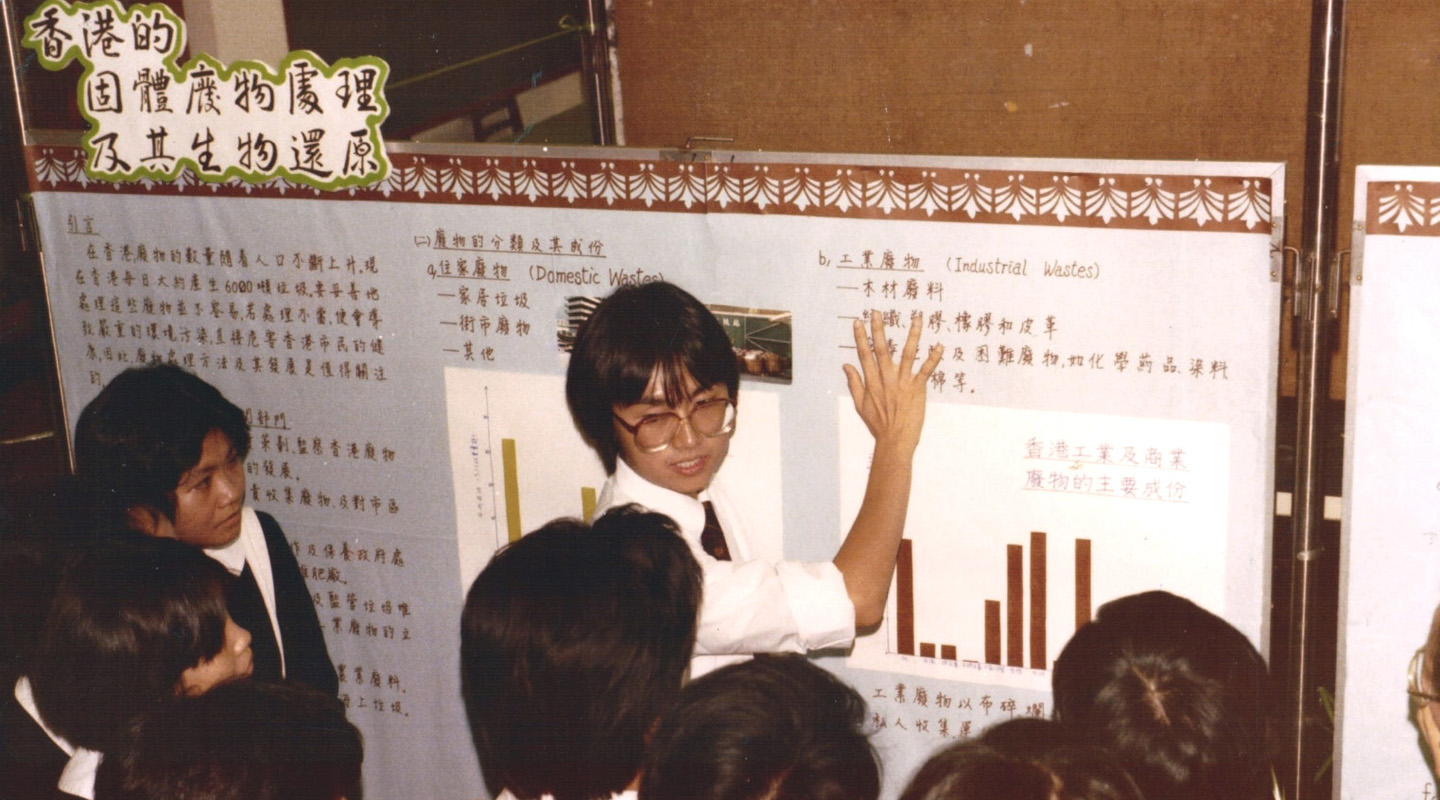

Ever since he was a boy, Prof. Chan Sun-on, an Associate Director of the School of Biomedical Sciences (SBS) and Head of New Asia College since this January, has been enchanted by the idea of there being a structure in living things, of different units coming together to make life possible. It was partly the cleverness of this grand design by nature that drew him into biology and subsequently anatomy and neuroscience, but it was also the beauty of it. Education in art was too much of a luxury to him, a child of a grassroots family, but there has always been an aesthetic side to his scientific mind. Unsurprisingly, CUHK appealed to that side of him when he moved on to university in 1982.

‘The campus was stunning. I was so impressed by its expanse.’

He would soon realize it was not just the campus that was expansive. Besides the repository of knowledge that was the then Department of Biology, he found the space to try out the many possibilities of university life other than being a biology major, possibilities he had never dreamt of. While studious, he was also an active member and leader in various student societies. And as a New Asia student—he would be the second alum of the College to serve as its head after the late Prof. Yu Ying-shih—he had the chance to ponder life after undergraduate studies.

‘Most New Asia students came from a modest, if not humble, background, and at New Asia they could find their way forward. This was a key reason I chose this College.’ For four years he lived in Chih Hsing Hall, summering in the then newly opened Grace Tien Hall. The halls were ‘cosy’, he fondly remembers, allowing him to focus on his academic work. Meanwhile, he had to take humanities courses even as a science major under the College General Education programme, which he would come to oversee many years later as a Dean of the College.

‘I didn’t get the point of studying humanities either at first,’ he admitted, echoing many students’ frustration with learning about art and culture. ‘But as I dived deeper into it, I started appreciating the works—which I still do in a different way now that I’m older—and getting something out of them. I suspect my pursuing a career in anatomy has to do with this renewed sense of beauty.’

Under the tutelage of his final-year project supervisor Prof. Vincent Ooi, who gave him access to an electron microscope and thereby to a deeper level of the magical fabric of life, he graduated with first-class honours. He then became one of the earlier Master’s students of the then Department of Anatomy under Prof. Jen Ling-sun, who inducted him into neuroscience. Winning the Croucher Scholarship in 1988, he set sail for a DPhil in Oxford. This change in milieu was the last step to forming his lifelong interest in the development of the visual pathway.

‘In terms of the physical setting, doing research at Oxford was not wildly different from working at CUHK. It was the great minds there that gave me new perspectives.’ Through the rigorous, weekly class presentations mandated by his supervisor, he figured out which part of life’s mystery he wants to devote himself to. With that mind, he returned to CUHK’s Department of Anatomy in 1991 and began his research and teaching career.

‘It was tough,’ he said of getting started as a researcher. ‘I was lucky to have the microscope Professor Jen had left me with. For some, it was just an empty bench to begin with.’ Teaching was easier, given how he had himself gone through the difficulties of dissecting a body as a student and knew what his students needed. For that he has been named the Faculty of Medicine’s Teacher of the Year 10 times since 2000. But there was still a problem.

‘We used to rely on unclaimed cadavers provided by the government, many of which are, for one thing, in poor condition. And let’s not forget supply can be tight with this kind of bodies, especially if there are other uses for them like in 2012, when the government needed them to test out the new cremator.’ And yet anatomy is very much a hands-on subject.

‘There’s no way textbooks alone can show you how an incision at a slightly different angle yields a totally different cut,’ said Professor Chan. ‘And without seeing the body in three dimensions, cutting open the muscle, finding the blood vessels and following the nerves, you can’t grasp how amazing life is.’

With nursing, pharmacy, biomedicine and Chinese medicine students needing cadavers as well as doctors in training, the University was at one point a mere six months away from running out of stock. The solution, drawn up by former Embalmer of the SBS Pasu Ng and Professor Chan in 2011, was the Silent Teacher programme, through which citizens can donate their bodies, teaching students the intricacies and beauty of life in death. Like an organism of its own, the programme brought together journalists and NGOs that spread the word, a cemetery that volunteers to honour the teachers and house their ashes when their mission is complete, and a surprisingly enthusiastic group of donors.

‘We were worried that the talk of death and dissecting bodies would be too much of a taboo. We were wrong.’ To understand what motivates body donations, the SBS partnered with Prof. Wallace Chan of the Department of Social Work and talked to several donors. By donating their bodies, the donors believed, they could make an impact even in afterlife and help advance medicine. Far from being ‘like a light going out’ as a Chinese proverb would have it, death can be a beacon of life, creating knowledge and bringing hope to the living.

‘I have utmost respect for the donors, and I hope my students do too,’ said Professor Chan. ‘There was a time when I would forget that the body was a human. I would look for blood vessels as if I’m solving a puzzle. But there’s so much more to it.’ He remembers a body with the duodenum removed and the intestines connected directly to the stomach: what kind of a disease must the person have had to warrant such an operation? What was it like for their family? Every scar has a story to tell, and to revere the donors by listening closely to those stories, Professor Chan believes, is every bit as important as to build a science upon their remains.

In his fascination with the structures of living things, his bridging the sciences, the arts and the human, his synthesis of life and death, and his embracing different people and possibilities, there is a belief in unity, a recurring vision of combining parts into an organic whole. Taking office as College Head at the height of the pandemic, though, he was often alone in his office for the first nine months, untethered, with the students being away.

‘It was hard to carry on with our mission to shepherd our students. We often wondered if we were really getting through to them online.’ It was only when the students returned in September, he half joked, his work as Head really started. For what is a university without its students?

But while the students were off, efforts—team efforts—in other areas went on. A year into his appointment, he has worked with the rest of the College administration to secure donations and reach out to alumni, all the while insisting on teaching anatomy face-to-face. Looking ahead, he wishes to push on with the exchange programmes, the scholarships and aids, and an endowment fund that would keep the College financially afloat.

‘I wasn’t sure at first if I was ready for this job, to be honest. Things will be difficult, I thought, but then I recalled the success of the Silent Teacher programme, and the College anthem rang in my head,’ he said. ‘March on I shall.’

By jasonyuen@cuhkcontents

Photos by Keith Hiro