Dear readers, With the launch of e-newsletter CUHK in Focus, CUHKUPDates has retired and this site will no longer be updated. To stay abreast of the University’s latest news, please go to https://focus.cuhk.edu.hk. Thank you.

Filial Piety Pays

David Faure tells you why being good to your parents makes perfect commercial sense

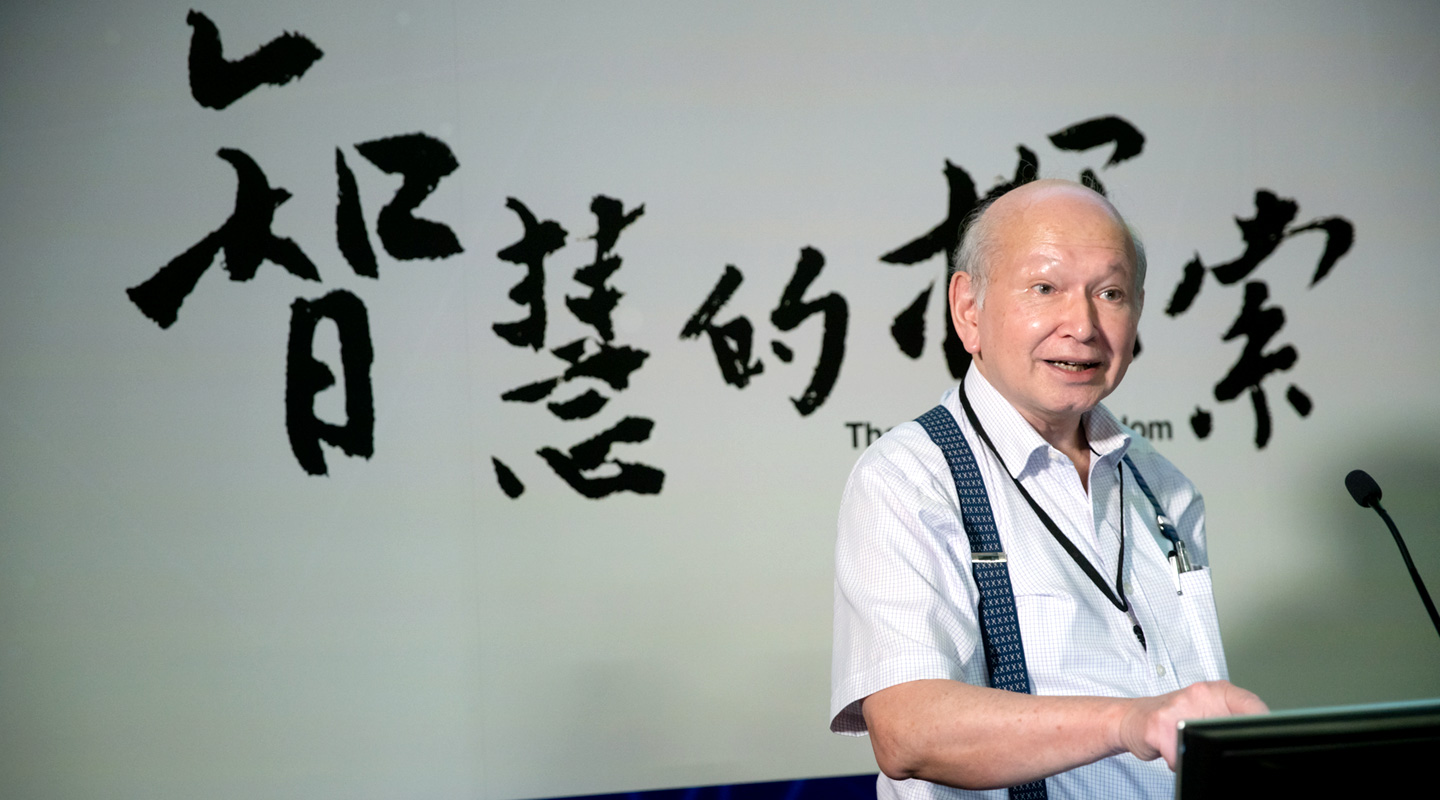

Filial piety is a key Confucian virtue but its discussions mostly centre around its moral content and ideological functions. With the historian’s eagle eye, Prof. David Faure saw its close ties to the economy in the Ming-Qing period. From studying the literature and genealogical records to making field trips to ancestral halls, he reconstructed history and ancient life in all their vividness. At the sixth instalment of ‘The Pursuit of Wisdom’ public lecture series held on 9 September, the Wei Lun Research Professor of History shared his research findings and insights under the title of ‘Filial Piety and Business Enterprise: Why is Filial Piety Good for Business?’. During the one-and-a-half-hour lecture cum Q&A, he held the audience of 200 faculty members, students and members of the public spellbound with dexterous treatment of some weighty matters.

Filial Piety as Safety Deposit

Professor Faure put forward two points to argue for the facilitating role played by filial piety in economic activities. He started off with a tomb epitaph from The Collected Works of Taihan, a seminal work on Chinese mercantile history by the Ming dynasty scholar-official Wang Daokun. The epitaph narrates how Cheng Changgong’s father, a salt merchant, had died during a business trip to Yangzhou and how Changgong, upon getting to where his father died to take care of his funeral, discovered that he was unable to retrieve the debts owed to the deceased. Worse still, upon returning to the hometown he found he was held liable for the debts his father owed to the folks back home. Selling his land and valuables, Changgong managed to settle the debts. After the three-year mourning period, he borrowed money from 10 village elders and set off to a new town to set up a money-lending business. Thanks to the low interest rate he charged for his loans, his business thrived.

What does filial piety have to do with business in the story? ‘On the surface, it seems to be a tale of filial responsibilities. But in fact, it works rather like a bank advertisement,’ quipped Professor Faure. ‘What Changgong operated was a banking business. A banker famed for his filial piety will keep his customers reassured. By insisting he would pay off his deceased father’s debts, he’s in fact making a statement that the cash deposits his customers placed with him were safe. By the same reasoning, if Changgong died himself, his son would honour his financial obligation.’ He continued, ‘Taking out loans is part of running a business. In order to be able to borrow, a borrower must convince the lender that his debt liability does not stop at his death. As there was no company law during the Ming and Qing periods, filial piety filled the gap nicely. It was like giving the status of a legal person to one’s business. Dead or alive, one is liable to one’s creditors. The close tie between filial piety and economic activities cannot be missed.’

Ancestors as Legal Persons

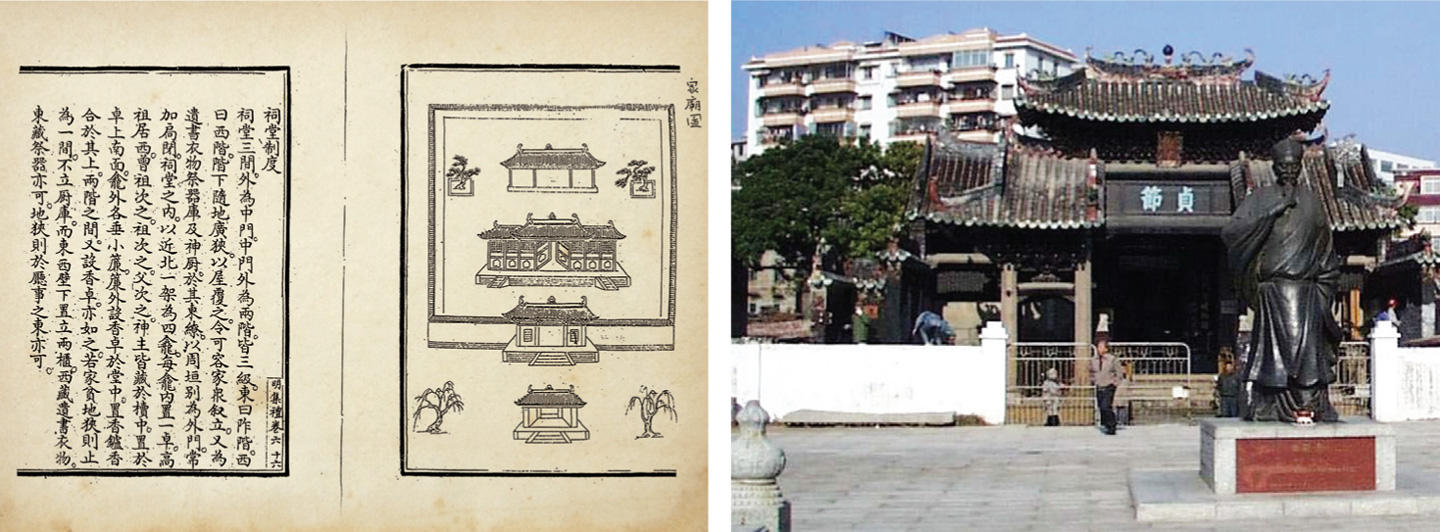

Professor Faure then went on to elaborate on his viewpoint that filial piety carries debt obligation across generations and explained how the ancients used filial piety as a moral force to establish clans with the ancestors at the core. Assets and estates were managed in the name of the ancestors, business partnerships forged, and clan members exhorted to accrue wealth for the clans. The average life expectancy at the time was around 30 years and the period shared by parents and their offspring was only about a decade. Thus filial piety was more about paying respects to deceased than to living parents. Prior to the Song dynasty, the eldest son would build a thatched hut next to his parents’ grave and keep vigil there for three years. Subsequently, as advocated by the neo-Confucians, the descendants could place ancestral tablets at home and pay their respects thereat. Clan networks and family histories developed from there. By the time of Emperor Jiajing’s reign in the Ming dynasty, it became fashionable for high-ranking officials to erect ancestral halls. Gradually, ancestral worship spread to the common people and became an important part of the clan system.

‘In China, making money for “private” gains was held in contempt. If this was so, how do you explain the prosperity enjoyed in the Ming and Qing periods?’ asked Professor Faure. The great neo-Confucian Zhu Xi held that the pursuit of fame and fortune was perfectly legitimate since it was done for the sake of the ancestors. Professor Faure continued, ‘Zhu Xi is like China’s Bernard Mandeville. The pursuit of a clan’s own interest would end up bringing benefits to the country and society.’ Filial piety in ancient China was a religious calling, and ancestral halls were like legal persons in the West which were tasked with the management of wealth.

An interesting example of this unison between the sacred and the secular was the annual ritual highlighted in the family instructions of the Ming scholar Huo Tao. During the ritual, the ancestral tablets were moved to the central hall, with the elders standing aside and the male children queuing on both sides to report, in descending order of age, on the lands and monies earned for the year. The elders would then mete out rewards. Although this ritual was later replaced by the ledger system, ancestral halls remained at the heart of wealth management. They were places where investment decisions were made and dividends distributed. To invest, clansmen formed partnerships with fellow clansmen, and took turns to manage the business at annual ancestral worships.

The Coming of the West

Ancestors were legal persons in southern China from the 16th to 18th centuries. Professor Faure observed, ‘Western society was built upon law which laid down the rules and regulations for its operation. But in China, rites and rituals were all that matters. People had much leeway to do what they wanted after the bowing was done.’ As a ritual, filial piety evolved with the times to become a vehicle conducive to business. But with the coming of the West to China, this vehicle became obsolete itself. Company law was introduced into the British colony of Hong Kong in 1865. Decades later in 1903, the Qing government promulgated the company law and since then, most family assets have been governed by it. ‘Up till today, clans are still around and so are the ancestral halls, only that they exist purely for ceremonial purposes and no longer manage the communal assets.’ Professor Faure concluded, ‘The story of filial piety and business has become a tale.’

Amy L.

This article was originally published in No. 544, Newsletter in Oct 2019.